On Christmas day, me and my vaguely Jewish family* joined the stereotype and, before our large dinner of Chinese food, went to the movies. Of course, being theatre dorks, there really was only one choice of film for the day. My mom wanted to see Meryl Streep, and I was dying to see pretty much everything about Into the Woods, so off we went.

My social media feed has since exploded with folks who saw it and their opinions of it. It’s kind of inevitable when you’re friends with a lot of theatre-types (many of whom are professionals and/or academics). For the most part, people have positive things to say about the experience with the occasional hater mixed in for good measure.

For my part? Haters gonna hate (…hate hate hate hate), but you just shake it off, Stephen Sondheim.

Into the Woods was a great film adaptation of a tricky complex story. The beauty of the play is in its tightness; the multitudes of tales that become inevitably intertwined by the greater dramatic events of Sondheim’s allegory. Director Rob Marshall and script/screenplay writer James Lapine did a masterful job of cutting the sometimes unwieldy piece into a slim two-hour film version that translated into the film medium with grace. Think about the scope of Into the Woods for a moment: you’ve got giants attacking townships, you’ve got birds pecking out peoples’ eyes, you’ve got cows dying and subsequently coming back to life who need to be milked onstage (and need to be able to eat props), you’ve got a character who needs to be cut open so that two other characters can come out of his belly, you’ve got a magic talking tree that showers gold and jewels and fashion onto a main character, you’ve got beanstalks growing, palaces thriving, balls balling, and markets selling. The show itself is cinematic in scale, and that’s even before you talk about taking it to the movies.

Film allowed Into the Woods to be its delightful self: quirky, magical, spectacular, and (yes) dark.

In the woods, you may encounter a Brussels Sprouts Swashbuckler who looks suspiciously like me…. alright, look, they shouldn’t put weapon-shaped food on the shelves if they don’t want people to fence with it, okay?

Now to the comment that the film was inevitably “Disneyfied”. Come on, people, what did you expect? You really think that a film being billed as a “mish-mosh of cute little fairy tales” would confront the reality of Sondheim’s allegory? Yes, “Hello, Little Girl” was a stranger danger song with no consequences beyond being followed home and eaten, and “I Know things Now” didn’t have the connotations of a sexual awakening. The Little Red plotline was kept very literal, at least on the surface. But let’s get real. Little Red Riding Hood is a story that bears the cultural burden of sexuality and has for hundreds of years; I hardly think that one film adaptation can undo all of that history. Besides which, the film doesn’t run from Sondheim’s lyrics. If you listen, even for a moment, the allegory is still there. The wolf still makes Red “feel excited… Well, excited and scared” and she still ponders “though scary is exciting, nice is different than good”. Johnny Depp as the wolf is slimy enough that I was made uncomfortable. I personally think that the sequence worked on a level innocent enough for kids, but dark enough for the adults looking for something more.

I’ve seen a lot of hubbub about the play being feminist or anti-feminist. I would like to remind audiences that this play isn’t new news. It debuted in 1986. If you want to have a discussion about what is/is not “feminist”, you need to go back and take a look at what else was being performed and/or talked about in that year, not this one. Moreover, the capable female characters who drive the plot can hardly be called “damsels”. Yes, Cinderella is a character in the play and yes, she still has a love story with a semi-disinterested Prince Charming who stands for all things machismo…. But this shouldn’t be surprising to anyone. Again, I refer you to the long history of the Cinderella myth and the myriad of popular culture icons and tales which have been produced about and around it. Sondheim’s Cindy is kind, driven, and determined; all of which are salient qualities which prove invaluable to her as she deftly navigates the woods. Let’s not forget that she leaves her “perfect happy ending” because she finds out that her husband has cheated on her and that she chooses to do this despite the fact that her life will be monumentally more difficult without the Prince’s wealth and power to back her.

Musically, I think the film lends more clarity to Sondheim’s complicated lyrics than any stage play I’ve ever seen. Because of the magic of cinema, every single word of these often tongue-twistered songs was crystalline (I finally understood a portion of the witch’s rap that, despite years of trying, I had not yet gotten… who knew that “rampion” was an edible root?). Because the filmmakers were able to slow down some of the thicker passages, they read much more readily to the waiting ear. If historically you’ve taken issue with Sondheim’s music, I’d strongly recommend giving this film a shot; I think it will clear up a lot for you (and perhaps be able to provide a gateway to some of his other work).

By far my favorite portion of the film was “Agony”. Film as a medium just lends itself much more readily to satiric melodrama than stage. Which is not to say it’s impossible to pull off on the stage, just slightly more difficult. Anyway, I was in stitches the entire number and it’s well worth the price of a ticket to see two handsome princes compete for audience attention amidst a slew of water effects. I was slightly sad they cut the reprise because the number was so good that I wanted them to do it again.

There were, I will say, a surprising number of children in the audience. Let me reiterate that while this film is based on fairy tales, it is not a children’s movie to any extent. It deals with heavy and dark topics (rape, murder, infidelity, body mutilation…), and has big scary man-crushing giants. Your young children will be bored and/or scared, and will spend the entire film kicking the back of someone’s seat while you sit there pondering what, exactly, it was that you thought you were getting into.

Really all I can say about the experience is, to quote the witch, “Go to the Woods!”. Just leave small children at home. And don’t expect something the play didn’t give you; that’s just not fair.

*We’re cultural Jews rather than folks with any particular religious bent.

This also complicates Hamlet’s killing of Polonius, as when he hears a rustling in the curtains of his mother’s bedchamber he could potentially believe it to be an undead foe and, thereby, shoot said foe in the head before it leapt out to attack. Polonius becomes an unfortunate victim of the country’s political strife as opposed to the sacrificial lamb of Hamlet’s madness.

This also complicates Hamlet’s killing of Polonius, as when he hears a rustling in the curtains of his mother’s bedchamber he could potentially believe it to be an undead foe and, thereby, shoot said foe in the head before it leapt out to attack. Polonius becomes an unfortunate victim of the country’s political strife as opposed to the sacrificial lamb of Hamlet’s madness.

best and sacrilegious at worst. At the same time, we well and truly wondered if this whole “marry a prince” thing wasn’t even more of a sham in his case than usual. I mean, after all, Ariel is the most gullible and least savvy of all the Disney princesses. It would be pretty easy to convince her that one was a prince with some impressive architecture, a personalized statue, and a French chef.

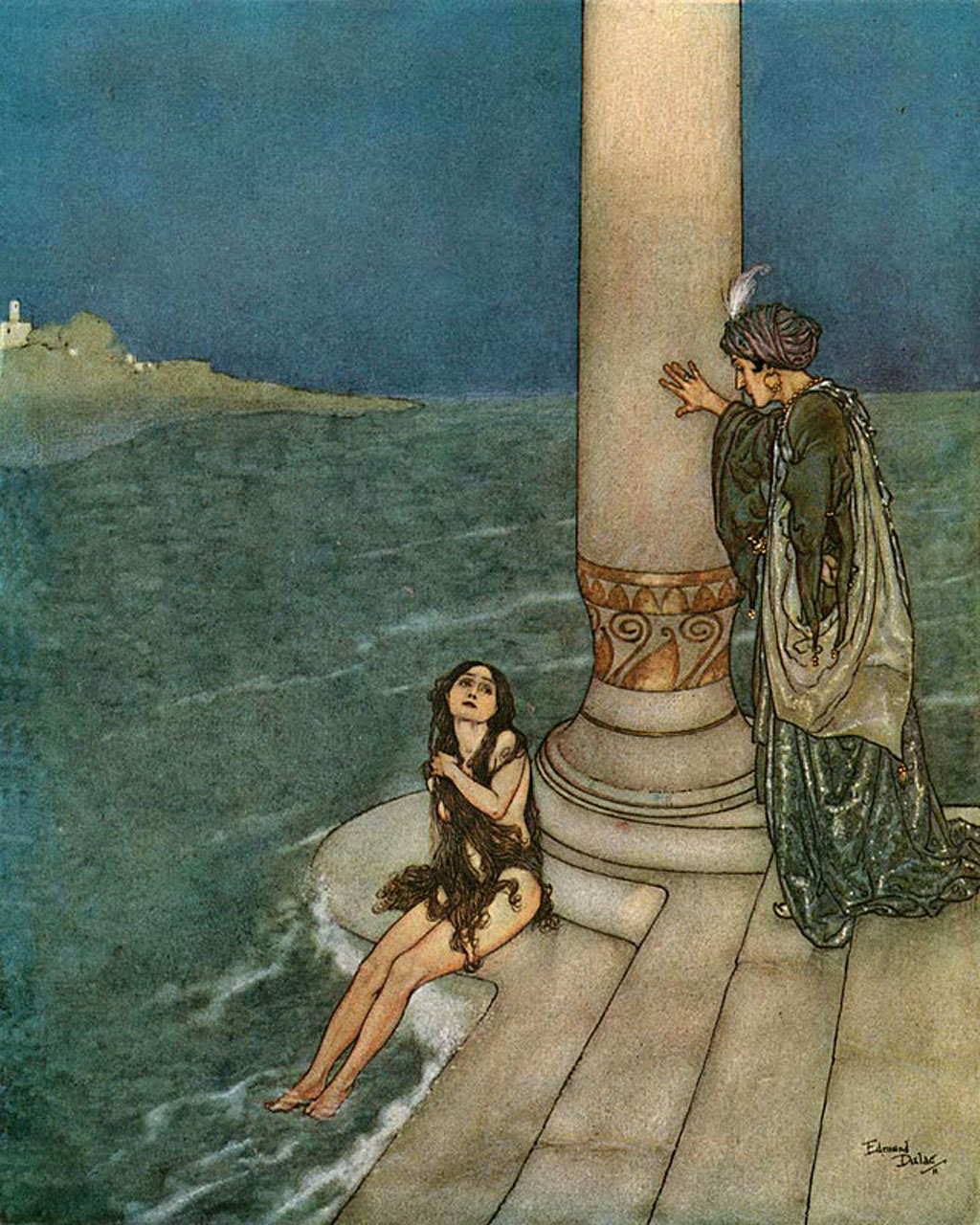

best and sacrilegious at worst. At the same time, we well and truly wondered if this whole “marry a prince” thing wasn’t even more of a sham in his case than usual. I mean, after all, Ariel is the most gullible and least savvy of all the Disney princesses. It would be pretty easy to convince her that one was a prince with some impressive architecture, a personalized statue, and a French chef. But this doesn’t take into account the ending of the fairy tale. Yes, of course, in the Disney version everyone lives happily ever after blah blah blah. But if you read the Hans Christian Anderson tale, things conclude a little differently. In the original tale, the Little Mermaid becomes human because she is told that humans have souls and can thus live forever even after they die. Mermaids, on the other hand, disintegrate into sea foam upon death. The nameless Little Mermaid strives to become human so that she too may obtain eternal life instead of waft into watery nothings. She buys a potion from the Sea Witch which will give her legs and make her dance unlike any human has ever danced, but will also make her feel as though with each step she is treading upon swords. In addition, she may only become truly human by marrying the Prince and thus obtaining half of his soul. If she fails to do this, then the morning after the Prince marries someone else the mermaid will melt into sea foam anyway.

But this doesn’t take into account the ending of the fairy tale. Yes, of course, in the Disney version everyone lives happily ever after blah blah blah. But if you read the Hans Christian Anderson tale, things conclude a little differently. In the original tale, the Little Mermaid becomes human because she is told that humans have souls and can thus live forever even after they die. Mermaids, on the other hand, disintegrate into sea foam upon death. The nameless Little Mermaid strives to become human so that she too may obtain eternal life instead of waft into watery nothings. She buys a potion from the Sea Witch which will give her legs and make her dance unlike any human has ever danced, but will also make her feel as though with each step she is treading upon swords. In addition, she may only become truly human by marrying the Prince and thus obtaining half of his soul. If she fails to do this, then the morning after the Prince marries someone else the mermaid will melt into sea foam anyway.

Hamlet an “American Shakespeare” (even though it did star Mel Gibson and what’s more American than that besides Sam the Eagle?), but we could term Luhrman’s 1996

Hamlet an “American Shakespeare” (even though it did star Mel Gibson and what’s more American than that besides Sam the Eagle?), but we could term Luhrman’s 1996