This weekend past, I was treated to a night in Paris. Nineteenth Century Paris, to be specific. The Players’ Ring in Portsmouth NH (a venue about which I have previously expressed my enthusiasm) put on a night of short plays inspire by Grand Guignol.

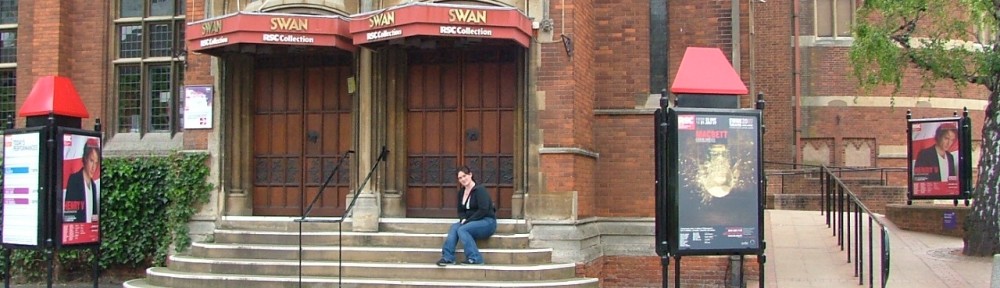

The Grand Guignol was a theatrical styling which takes its name from its birthplace at the Le Théâtre du Grand-Guignol (a specific theatre in Paris;

original poster from the Grand Guignol

open from 1897-1962). Grand Guignol (“Guignol” was the name of a Punch-and-Judy style puppet, so “Grand Guignol” literally means “Great Puppet-show”) is characterized by its realistic violence and horror, often featuring strongly sexual themes and violence done to women. Live at the Grand Guignol, you could see disemboweling, tortures, rapes, murder, and all manner of senseless blood and violence. Principle Playwright André de Lorde often judged the success of his plays based upon how many people in the audience fainted or vomited during a given performance.

The Players’ Ring produced a series of three one-acts which ranged from the shocking awful (and I mean that in the sense of value-judgment, not sublimity) to the titillating wonderful. The first show, a new work entitled The Box, fell flat. Its premise: a couple is unable to conceive. He is abusive, eccentric, and more-than-a-little crazy. She is a witch. No, literally, with tea leaves and summoning and everything. She summons the ghost of his dead father to halt what she perceives as a “curse upon his line”. The ghost arrives, much to the horror of the husband, and ravages the wife onstage, then departs. He, horrified at what she may have conceived during this encounter, kills her, then recites a line from Hamlet.

The acting was sub-par, the costuming was hilarious (the drowned father wore a full-head mask that looked like a particularly enthusiastic trick-or-treater rather than a being of horror), and the play had one fundamental problem: unless you’re actually going to have two actors doing the deed (alternately some sort of interpretive dance or something), don’t show sex onstage. Everyone in the audience has done it, everyone has seen it, we’re going to notice if it’s even a little “off” and at that point all it looks like is awkward body palpitations. This is especially true in a small house (which the Players’ Ring is) and ESPECIALLY true in three-quarter seating arrangement (which the Players’ Ring has). This particular stage set-up, so wonderful for intimate theatre, leaves you no margin for fudge; the audience can see EVERYTHING (this will come into play later). In the case of “sex”, it means we can see where you’re trying to cover your butts (literally).

My companions disagreed with me on this part. One of them suggested that, during the rape, there were people laughing in the audience because they were uncomfortable. And what was Grand Guignol if not theatre to make people uncomfortable? That, to him, meant that the rape did its job.

…I just assumed they were laughing because what we were seeing was so utterly ridiculous. Well. We all have our opinions.

The second piece (entitled A Crime in the Madhouse) was an adaptation of an original Grand Guignol piece (entitled Un Crime dans une Maison de Fous). It depicted a woman held improperly in a mad house by her asylum-owning ex husband. She begs to be let out, or at least to a different room, because she says the neighboring lunatics have broken into her room at night. The doctor says that this is impossible since once can’t even lift her head from a bed and the other is raging mad. The woman persists. The doctor says he will have her moved tomorrow, and that night the nurse will not leave her. The nurse insists her place is at vigil beside the body of an inmate who recently died and, despite the doctor’s promptings, leaves the woman’s room periodically.

Famous image of an onstage lobotomy given during a GG performance

Sure enough, creepy next-door lunatics shamble into her room and pluck out her eyes with a knitting needle, leaving the woman to die and the nurse to irritatedly monologue over her body.

This one was creepy. The girls playing the next-door lunatics (especially the paralysis victim) were so unpredictable and malicious that I still have to summon mental images of Ru Paul to protect me from their nightmarish forms. The eyeball prop was utterly and wonderfully realistic, and the acting was spot-on.

The only problem in this play was, well, the space. As mentioned above, a three-quarter house leaves nothing to the imagination. In this case, since I was sitting on the side, it meant that I could see every move made by the girls during the eye-dashing. While I of squeamish stomach was grateful to see the strings behind the curtain, I of fight-director illusionist definitely could have given some tips to let this go the extra mile. Because believe me, if I hadn’t seen the switch and blood packets, it would have haunted me for a good long time.

The third play (another new work by E. Christopher Clark) was simply spectacular. French farce devolved into hideous torture scene, this play really showed a sense of the audience’s levers and played upon them with delightful force. The story was such: a man goes to see a doctor to receive vaccines for an up-and-coming business trip. Turns out, the man and the nurse (also the doctor’s wife) have had an affair and the doctor is not a very good husband (always busy and away on business trips researching strange illnesses). The nurse and man plot to kill the doctor and run away together. The doctor, not a likeable dithering idiot as he is so good at pretending to be, overhears their plot through the walls, kills his wife, then slowly tortures the man to death onstage. When through, the doctor has a drink of tea… the tea which the man had poisoned in an effort to kill the doctor. Doc dies. Curtain down.

The director knew exactly where to punch this. Knowing that the second half of the vignette would be blood and gore (and knowing that the audience also knew this), he utilized the first half of the play to set up characters whom we loved. The nurse and patient had adorable French accents and posed melodramatically at every opportunity they had. The doctor played doddering American Fool to the nines. A game ensued between director and audience: when would this go poorly, how poorly would it go, and when (exactly) would you need those ponchos in the splatter section?

The answer was “as suddenly as the doctor slit his wife’s throat and, by means of an air cannon and chocolate syrup, splattered blood over a third of the audience”. Again, the only teensy problem with this show was the angles. Since I was sitting on the side, I saw every one of the numerous bladders and squibs that the doctor utilized in torturing his victim. I knew when he changed bladders, I know where the blood bladders were hidden, and as a result I knew when something awful was about to happen.

That lack of surprise meant that a great deal of the shock was taken away for me. However, I was willing to overlook it because the actors and the direction were just so darned charming.

When the dust settled, we were left with three bloodied bodies onstage and the age-old question: how do we deal with this situation? In the theatre (especially a small house), you have two options: carry them off, or blackout and have them walk off which, obviously, completely breaks the illusion you’ve worked so hard to create.

In addition, we were left with an important theatrical factor to recognize: what do we do now? When a group of people has seen something horrible, even something “fake” horrible, there’s a great deal of tension in the theatre. Cruelty and violence are hard to stomach and, even in our inured modern society, seeing it live still leaves us raw on the inside. It can be very damaging to an audience to be suddenly jarred from something like this. Don’t believe me? Go see a production of Titus and tell me that you’re not feeling just a little queasy by the end of it (or, more likely, like you’ve been run over by the Bard Bus). I dare you.

Grand Guignolrecognized this problem and dealt with it as Shakespeare did: with a classical jig! The Early Modern Theatre capped off every performance (tragedy or comedy) with a full-cast song and dance number (often upbeat and exciting). In a brilliant move on the part of the Players’

Wil Kempe dancing a jig to pipe and tabour

Ring, they took this cue and, just as we were left wondering “well shit, there are three bodies on the stage, what now?” the casts of each show skipped blithely onstage singing a happy ditty written by the brilliant Shel Silverstein (You’re Always Welcome at our House).

You can bet the entire audience was laughing by the end of the song, especially when the bodies onstage stood up (blood and all) and began singing along. So simply did the Players’ Ring soothe our raw emotions and re-assure us that yes, it was alright to like this and no, no actors were harmed during the making of this play.

Unfortunately, this show has seen its run. There are, however, several other late-night productions appearing at The Players’ Ring over the course of the next few weeks (including Mysterious Subtext Theatre, a take on MST3K, and Dungeons and Dragons Live! which is, as far as I can tell, exactly what it sounds like). Check them out!

This also complicates Hamlet’s killing of Polonius, as when he hears a rustling in the curtains of his mother’s bedchamber he could potentially believe it to be an undead foe and, thereby, shoot said foe in the head before it leapt out to attack. Polonius becomes an unfortunate victim of the country’s political strife as opposed to the sacrificial lamb of Hamlet’s madness.

This also complicates Hamlet’s killing of Polonius, as when he hears a rustling in the curtains of his mother’s bedchamber he could potentially believe it to be an undead foe and, thereby, shoot said foe in the head before it leapt out to attack. Polonius becomes an unfortunate victim of the country’s political strife as opposed to the sacrificial lamb of Hamlet’s madness.

was new and different because Stomeham coupled their adult company with their teen company so the adults played adults and the teens played teens.

was new and different because Stomeham coupled their adult company with their teen company so the adults played adults and the teens played teens.