Yesterday morning, I awoke to a wonderful e-mail in my inbox. The e-mail (from a dear friend) directed me to this link. The day proceeded to unfold in a series of facebook postings and overall internet twitter about the project and, of course, the wonderful people in my life who recognize what a complete nerd I am and believe that I absolutely must know about this immediately.

In case you haven’t heard yet (or clicked the link above), the news has been confirmed: Joss Whedon secretly filmed a version of Much Ado About Nothing during his one-month vacation from “The Avengers”. The film’s website (including initial press release) is located here.

Well this is an exciting move for American Shakespeare.

First things first, let’s tackle Whedon’s choice to take on a Shakespeare film adaptation. The King of the modern Shakespeare film is without a doubt Mister Kenneth Branagh. Branagh’s films are lush and well publicized and not lacking in technique or tradition. Branagh is undoubtedly a pivotal part of the modern Shakespeare tradition due to the audiences he has brought to the Bard’s work. However. Despite the fact that well-known American actors have worked on Branagh films (Alicia Silverstone’s Princess, Kevin Kline’s Jaques, and who could forget Keanu’s Don John?), Branagh is unrelentingly an Irishman working in an Englishman’s industry. His films, despite their popularity in the US, are certainly part of our cultural tradition though not a part of our Shakespeare tradition.

There have been American Shakespeare films before. I am loathe to call Zeffirelli’s 1990 Hamlet an “American Shakespeare” (even though it did star Mel Gibson and what’s more American than that besides Sam the Eagle?), but we could term Luhrman’s 1996 abomination of a film as such. In addition, Julie Taymore has her 2010 The Tempest and her 1999 Titus, the Radford Merchant of Venice staring Al Pacino as Shylock (2004), Olivia Parker’s 1995 Othello starring Laurence Fishburne, Michael Hoffman’s 1999 Midsummer with Kevin Klein, and (historically) Max Reinhardt’s Dream of 1935. If we think about the entire Shakespeare on Film opus, that’s a pretty puny lot that Americans have managed to produce.

Hamlet an “American Shakespeare” (even though it did star Mel Gibson and what’s more American than that besides Sam the Eagle?), but we could term Luhrman’s 1996 abomination of a film as such. In addition, Julie Taymore has her 2010 The Tempest and her 1999 Titus, the Radford Merchant of Venice staring Al Pacino as Shylock (2004), Olivia Parker’s 1995 Othello starring Laurence Fishburne, Michael Hoffman’s 1999 Midsummer with Kevin Klein, and (historically) Max Reinhardt’s Dream of 1935. If we think about the entire Shakespeare on Film opus, that’s a pretty puny lot that Americans have managed to produce.

I would argue that Whedon’s version will be the first modern purely American Shakespeare. In addition to American acting and directing sensibilities, the instinct to release it via the internet (a la “Dr. Horrible’s Sing-Along Blog”) also brands it as a creation of contemporary American culture publicized via a globalized world. In short; this could be huge. This could be international. This could be great.

And it’s an attempt by our budding Shakespeare tradition to break free from stodgy molds and create something new.

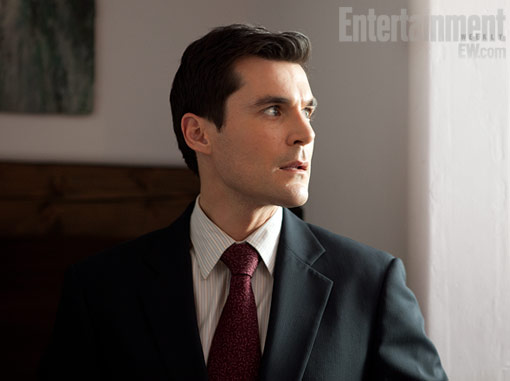

Maher as Don John. You work that suit, Simon!

Undoubtedly, Whedon’s production is going to be compared to Branagh’s ’93 film and only time (and a full review) can tell how it will hold up. My initial impressions are better already – who wouldn’t take Sean Maher over Keanu?

Whedon’s choice in play to film is not unexpected given his canon. He has long been attracted to strong female leads (“Buffy”, “Doll’s House”, “Firefly”), his humor is witty and quirky, and he seems particularly fascinated by soldiers and war stories. For all of these things, Much Ado fits the bill. I am particularly looking forward to Nathan Fillion’s performance of Dogberry and Sean Maher’s Don John (who will, with no doubt, overtake Keanu’s California surfer boy with the talent contained in his pinky finger… really, folks, it doesn’t take much to outstrip an actor with one feeling).

There are two things that makes me slightly nervous about the enterprise: one, there is no recognizable dramaturge working with Whedon. While I don’t wish to belittle the intelligence of a man whose creativity and artistry I well respect, I will say that it is a haphazard move to work on a film of what is essentially a period piece without consulting someone who really knows what they are talking about. To a modern director (especially someone working in film with what is traditionally a stage medium), a good dramaturge can be a godsend. Who else is going to contextualize the piece within its historical and modern importance? Who else is going to do the research as to what random words mean and how they should be presented? Who else is going to deal with dimwit actors who can’t seem to find a grasp of the text? Whedon isn’t a Shakespeare virgin, but even the best need some backup. In an interview, Whedon confessed to some trepidation over the title “Much Ado About Nothing”. “Well, I have nothing to say about nothing” he said. Of course, after many re-reads of the script he realized that this title isn’t really what the play is about. This sort of problem is precisely why you need a good dramaturge; somehow who has researched this stuff and can explain the connections. Someone who can steer you clear of these misconceptions. Someone who knows their Shakespeare, darnit!

My second bit of nervousness has to do with the relative inexperience of film actors with Shakespearean text. I’m not saying that there’s no possibility of amateurs being brilliant, I’m just saying that without proper vocal and text coaching such things have proven in the past to be disastrous (just look at Leo and Claire in Luhrman’s film if you really want proof of a train wreck).

For that, I will be looking forward to seeing Wheedon’s directing style within this piece as

Amy Acker and Alexis Denisof as Beatrice and Benedick

well as a certain loyalty to the text. Too often, hip American directors superimpose their vision and words over text which has, for hundreds of years, spoken for itself. Whedon’s actors, while all amazing in their own right, have never struck me as the most disciplined lot. It will be a true test of their worth to see how well they manage when a certain sort of freedom is stripped from them. In addition, much of Whedon’s work relies upon acting between the lines; pregnant pauses, meaningful glances, physical humor unalluded to within the text of the script… All of this must go with Shakespeare. Shakespeare is entirely about acting on the lines. There is no subtext in Shakespeare. Everything you need to make a successful and entertaining production is right there. Trusting the Bard is the only way to create a meaningful Shakespeare (lack of this, by the by, was Luhrman’s greatest failing).

If Whedon and his gang can overcome the desire to insert between Shakespeare’s text, I truly believe that this will be a film for the ages.

I am very much looking forward to seeing it.