Ah the beginning of a new semester. Fresh new faces, a slew of new names to learn, and new classrooms full of new people to meet knowing that they’ve previously googled me.

As you know if you’ve done any reading of this blog, I keep and curate an extremely active digital presence. I also keep and curate a digital presence for several major professional organizations, and have helped even more begin their adventures into the digital world.

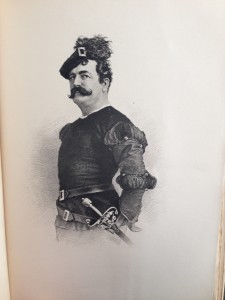

one of the more awesome shots that pops up in my google image search; me kicking butt at the Summer Sling this year

It’s not uncommon for me to meet people who are gun-shy about the internet. They think that curating an online persona entails revealing too much of their private lives, or somehow exposing themselves in a way they aren’t comfortable with.

The fact is this: in the digital era, you will have an internet presence. Depending upon the popularity of your name, that presence may or may not be immediately linked with you personally. Never doubt this, however: that presence can either harm or help you, and curating that presence is taking control of what happens when someone types your name into google.

Because, let’s face it, what do people do the minute an unfamiliar name crosses their desk? How to employers verify (or investigate) claims of expertise or previous employment? How does anyone know anything these days?

Taking your digital presence into your own hands is taking the power back from the system. By actively curating, you craft a presence that makes you more legitimate, more desirable, and more accessible.

In order to keep this presence clean and free of “unmentionable” (or at least unprofessional) personal information, the key is to create (and hold yourself accountable) to a set of personal protocol for social networking. Before I share anything on the internet, I take myself through a series of questions about the content. If the content doesn’t measure up to my protocol standards, I either find a way to share it that is protected by security measures (like facebook permissions groups, password walls, or private e-mails), or keep it to myself.

Here is my list of primary content questions that I make myself ask about anything before I post it to the internet:

Would you be comfortable with someone reading this (tweet, status, blog, etc.) out loud at a job interview?

Would you be comfortable with your students knowing these things?

Would you be comfortable with this content being read aloud to your tenure review board?

These are my “red flag” questions; i.e.: if the answer to any one of these questions is “no”, the content is not fit to be posted publicly. If the content is green-lit by these standards, I further ask myself:

Are you currently of sound mind? (…i.e.: have you slept enough? Had your coffee yet today? Eaten recently? All of these are key factors that could influence good decision-making).

Have you re-read this content to check for grammar, spelling, and proper attribution?

Have you fact-checked this content with a reliable source?

These questions are “shelf it” questions; if I answer “no” to any of them, I can’t post the

Pro tip: google image will also pull from your youtube account; here’s a still from some action vid of me cracking my bullwhip courtesy of this feature

content until that answer turns into a “yes”. They won’t necessarily prevent me from posting something, but they certainly do some work to ensure the quality of my posts.

So as you begin to meet fresh faces this year, consider implementing your own set of standards for what the internet has to say about you. And, if you’re not already, consider putting your own two cents into the mix. I guarantee that, with some effort, the long run will be worth it.