So I had my first rehearsal yesterday.

Boy oh boy am I rusty on being an actor.

First things first: It’s been approximately four years since I have taken the stage, and much longer than that since I’ve played a role of any particular note (my last role was Antonio/the Captain in Twelfth Night). I’ve only played a leading role once or twice and at least one of those times was when I was young enough that my age registered in the single digits.

My current directors had requested that we make an attempt to be off book by the first rehearsal. An attempt was made, but I only accomplished two fifths of the goal.

The process of line learning is an arduous business made even more arduous when you are learning Shakespeare for a few reasons. Reason one: you need to be word perfect. Reason two: the strange sentence structure will mess with your head and cause you to add/subtract random words that you think should go in there but in actuality have no business with the bard. Reason three: because of aforementioned bizarro sentence structure, there exists no parallel structure in what you are saying and, since the human brain likes patterns, you can easily find yourself falling into the trap of creating parallel structure (see reason one). Reason four applicable to Rosalind: so much of what she says is in Prose. Prose is approximately ten times more difficult to learn than Verse.

Today’s brief lesson in Shakespeare: knowing the difference between Prose and Verse.

Verse is the more familiar poetic form that we often affiliate with

my script all marked up. It will be more marked up before this is all over.

Shakespeare. It’s written in meter, sometimes written in rhyme. Identifying Verse is extremely easy as each line will begin with a capital letter, and the lines themselves will be shorter since they have to conform to the structure of poetic meter. Here’s what verse looks like:

ROSALIND:

My father loved Sir Rowland as his soul,

And all the world was of my father’s mind:

Had I before known this young man his son,

I should have given him tears unto entreaties,

Ere he should thus have ventured.

(As You Like It, 1.2)

In the case of Shakespeare, the poetic meter used more often than note is Iambic Pentameter. Iambic Pentameter refers to a line which contains five (Pent) Iambs. An iamb is a series of two syllables – the first unstressed, the second stressed. Like this:

ROSALIND:

I pray / you, do / not fall / in love / with me,

For I / am fal / ser than / vows made / in wine…

(As You Like It, 3.5)

What this means is that the line has a heartbeat. Da-DUM. When you are speaking a line written in Verse, you can feel when you’re adding or subtracting words because the line has a natural cadence and rhythm to it.

Prose, on the other hand, is a completely different story. Prose is written like modern sentences; flowing together one after the other. Like this:

ROSALIND:

No, faith, die by attorney. The poor world is

almost six thousand years old, and in all this time

there was not any man died in his own person,

videlicit, in a love-cause.

(As You Like It, 4.1)

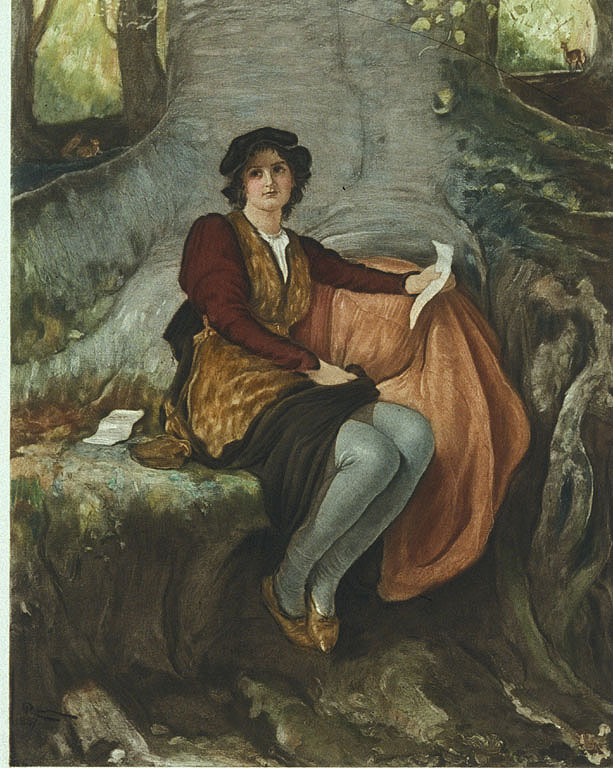

“Rosalind” by Robert Walker Macbeth, 1888

Prose has no set rhythm (though, it is Shakespeare, he often plays word tricks with his lines). Since Prose isn’t spoken under the pressure of iambic pentameter, it doesn’t conform to anything by way of regularity.

Guess which form most of Rosalind’s lines are in?

Now, Verse is a form of speech most often used by courtly characters, learned characters, characters who are in love, characters who speak directly from the soul, or characters who need to express something complicated. Because Rosalind spends the majority of the play in disguise, she also dumbs down her speech to Prose – the form used by clowns (not fools, fools generally speak in Verse), commoners, and normal people. Rosalind is capable of speaking in Verse, and does so when she is in the court and when she is dealing with Phebe (a mark of her inextricable snobbery), but 85% of her lines are Prose.

This has made her a ridiculously difficult part to learn. Compound this trouble with the fact that I learn best on my feet and tend to prefer learning my lines while doing scenes rather than in a vacuum at home, and this endeavor has been immensely challenging for me.

But I’m getting there.

Rehearsals go into full swing next week and I can’t be more excited. It’s a talented lot we have, and I’m extremely happy to be able to have the chance to work with them.

Stay tuned!

While I am sure you are up to the challenge I think you also learn well when surrounded by those as impassioned as you are for not only the characters but the depth of writing. Learning in a vacuum is like hitting a ball in a backyard, learning the mechanics, preparing your stance and finding your swing…. there is no faster teacher than doing so in an actual game.

You’ll do great but if any of us can be of help don’t hesitate to ask. I love theater but know less about Will and his writings than your BFF as an FYI.