So we had our first “real” rehearsal last night. By “real” rehearsal, I mean we were up, on our feet, with text, doing things and playing around.

We worked I.ii, I.iii, and a little bit of IV.iii. What this meant was a lot of work with my Celia.

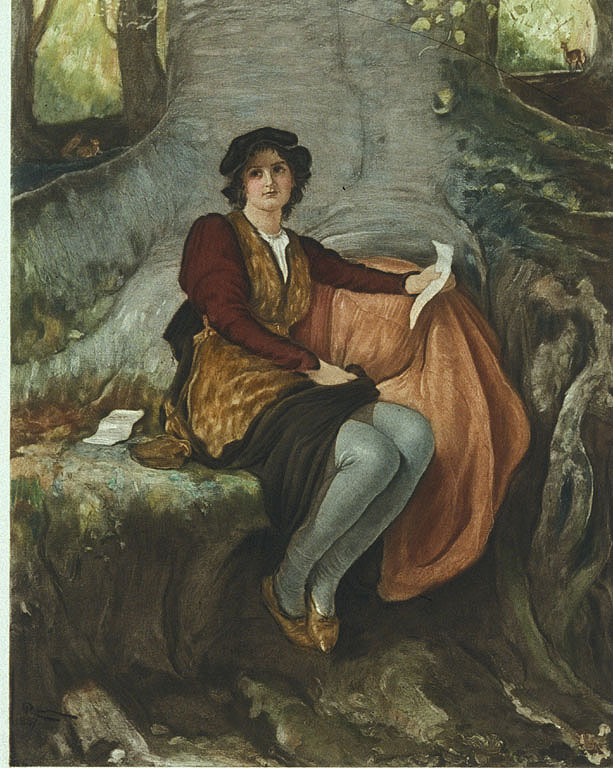

There are several keystones of a good As you Like it and one of them is the relationship between Rosalind and Celia. These two ladies rack a great deal of stage time, and almost all of it is together. If their relationship is off, it can throw the entire play off kilter. Suddenly, the plan to go into the forest no longer makes sense. Suddenly, the cross-dressing is just a hackneyed attempt at a laugh. Suddenly, the play lacks real heart.

So it was really important to me that I do my best to make this relationship work. Luckily, I didn’t have to work too hard since my Celia is spectacular.

Her name is Ashley, and she is a tiny tiny woman. This is great because it makes me look “more than common tall” (which the texts demands that Rosalind be and which, at 5’5”, I most certainly am not). She’s also a fire cracker; feisty and sassy one minute, and soothing and lovely the next. She brings real heart to Celia while still bringing the fire that so often can get lost in a wash of dumb blonde. I’m really enjoying working with her.

Another great thing about this production is that we are actually getting to work in the space from day one. Since the Winthrop playmakers own the theatre, and since we are the only show they are producing right now, we have the run of the place. This is an extremely uncommon arrangement. One of the most expensive things about producing is renting space and, as such, space is rented for as little time as possible. Time in the actual theatre is generally limited to a week’s of rehearsals before the show goes up (if you’re lucky; if you’re unlucky you may only get a day or two).

This is the first time I’ve been in a show since my high school days that I’ve actually gotten to work on the stage starting day one.

I can already tell some of the challenges we are going to face. It’s a proscenium house,

The outside of the theatre. Told ya it was a church.

which is automatically limiting since it means that any stage picture we create will be two-dimensional. Luckily, there are some nice roomy aisles in the house and convenient steps for us to use, so the house itself becomes viable playspace. Still, making dynamic scenes that don’t pattern and re-pattern themselves is going to prove challenging.

The acoustics in this house are particularly good since it’s relatively small and a converted chapel. In my experience, converted holy spaces tend to have the best acoustic resonance since the only thing that makes a Latin sermon more snooze-worthy is not being able to hear half of it.

My line-learning efforts have proved fruitful and I’m off book for three acts now. I’m beginning to delve into Act III which is extremely challenging since I’m onstage for most of it, and driving the action of most of it. The good news is that I’ve seen many of the scenes from this act done before, so I have some sense memory of them. Learning the first half of III.ii was like coming home to embrace an old friend. I can’t even begin to tell you how many times I’ve seen this scene done in classes and workshops and wanted to be part of it; it’s just so fun and light-hearted. There’s so much joy in it. I’m extremely excited to rehearse it.

Since we did play with IV.iii tonight, I was again reminded of the importance of a Stage Combatant in the cast of a show like this. “Violence” onstage is not limited to sword fighting; stage violence is any moment in which an actor comes into physical contact with another actor. If you know the play, you will know that in IV.iii Rosalind faints. When we arrived at that point in rehearsal, I received no instruction on how to do so and was expected to pull something out of my bag of tricks. Luckily, I have the training to accomplish a vast array of faints and falls without injuring myself, but there’s the very real possibility that a Rosalind might not know how to fall. It’s harder than it looks, trust me. And making it look convincing without the “ow” takes practice and a mat for your first few tries.

In any case, there was a bouquet of options I was able to offer my director: straight or silly? Prat fall or Victorian Lady faint? A little more thud, or a silent fall? All things which must be carefully considered in crafting what turns out to be a pretty comical moment in the scene.

My good friend Angelo (Oliver) and I decided to take a swing before rehearsal.

I’m also lucky in that my Oliver is a dear old friend, and so we were able to work the physical portions together and add to them as we go along. And Celia was along for the ride, just like a pro.

On the whole, I’m very happy with how things went last evening and I’m very much looking forward to more.

…except it means I need to learn more of this darned prose…

…drat.