Over the weekend, I found this post on HowlRound and it elicited a huge reaction from me. The story of my relationship with professional theatre definitely has a happy ending, but bears some striking similarities to the tale of Mr. Keel.

I’ve been a professional theatre-maker for most of my life. I had the good fortune to attend a performing arts high school, which gave me the training and know-how I needed to navigate New York’s professional scene from a very young age. I bought backstage every week; sent out headshots, resumes, and cover letters; went on auditions; booked jobs; and generally worked my tail off while going to high school. By the time I got to college, I was jaded enough to know that a four-year conservatory program wasn’t going to give me what I wanted; a full time career in the arts wasn’t about spending my college tuition money cultivating my art, it was about figuring out how to work with what I had. I bypassed the BFA in favor of a more “real world marketable” degree and continued my training on the side at some of New York’s many studios where such things were possible.

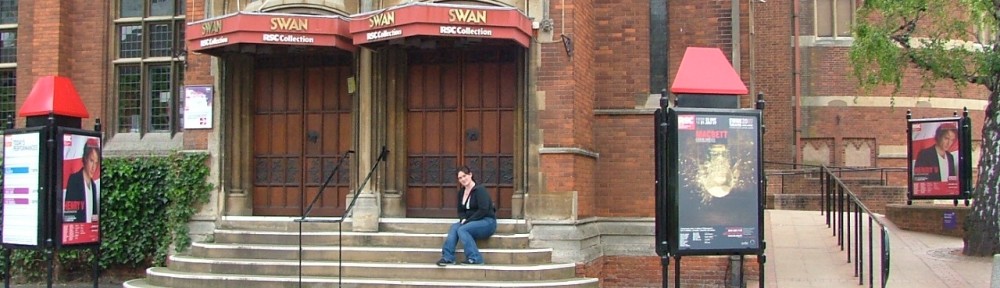

After college, I worked my way around a bit (both in and out of the field). It was during a

High school me performing in “The Laramie Project”

conservatory production of Twelfth Night at a big-name regional theatre that I experienced my career turning point. While I had learned a great many things from this company over the years (having trained and worked there several times), it was clear that the program I was embroiled in at that moment didn’t understand me, didn’t encourage me, and didn’t feed my art. I had found myself in an artistic dead space; while those around me could hear their ideas and emotions “resound” within the conservatory, mine were continually disregarded and devalued. Needless to say, I was depressed and lonely and just wanted to finish up my time there so I could go home, lick my wounds, and figure out if this whole “full time theatre professional” thing was really going to work out for the rest of my life. It came to a head one evening during a tech rehearsal in which the director, frustrated with the speed at which tech was running, stopped rehearsal to tell me (in front of the entire cast and production team) that I was “an idiot” for not understanding his clear-as-mud direction, and further elucidating how stupid I must be if I couldn’t comprehend what he was telling me.

That pretty much convinced me that I wasn’t cut out to be an actor. It wasn’t okay that someone felt like they could talk to me that way, it wasn’t okay that I had no recourse about it (what was I going to do, walk out of the rehearsal and never return?), and it wasn’t okay that if I did decide to take action I would be the one bearing the negative label for the rest of my career as someone who was “difficult to work with”. I finished the run, but packed in the trunk and retired from the stage, refocusing my energies on other things.

It took many years for me to want to come back to theatre. While I loved so many things about it, the negatives far outweighed the positives. Professional theatre seemed like a pleasant daydream; good for the young and naïve but in actuality not realistic if you wanted to work, live, and be treated like a human being. Hence my relationship with the term “professional” became fraught; professionalism and the lessons I learned as a professional theatre-maker were things I carried with me in all walks of life. Be fifteen minutes early, come prepared with your work, have a pencil on hand to take notes, bring a water bottle, make eye contact, communicate clearly… I could go on. But for that, being a full-time professional actor had baggage that I simply didn’t want to carry with me. I was angry. I was hurt. I was upset that I had spent so long hanging my hopes on a star that turned out to be a time bomb.

For me, after several years of staying away altogether and then an easy transition back into the theatre via teaching and mentoring (which I absolutely love), I can once again say that I am a “theatre professional” (or was I always a “professional” and just took some time off?). As you know, I now have several levels of theatrical involvement, all of which I consider “professional” engagements: I review, I fight direct, I dramaturge, I text coach, I teach, and (when the mood hits, but only when the mood hits), I perform. But that’s not the case for everyone. I’m definitely one of the lucky ones.

And I think that this, unfortunately, isn’t an uncommon experience. I think there are a fair number of folks who wanted to go pro, trained to go pro, and for one reason or another had to back away from the life of full-time professional theatre-making. Unfortunately, this experience can leave a bad taste in the mouth; we all have our reasons for breaking up with Thespis. As with any breakup, it’s painful and unpleasant, and the way that you handle that pain will determine your attitude about running into your ex at parties.

More often than not, performing looks way more like this for me these days. (Photo courtesy of Al Foote II Theatrical Photography)

There are some who return to the theatre on an amateur level because they simply love making art. Theatre is a part of their blood, and just because they didn’t want to do it professionally doesn’t mean they should stop entirely. This is the best kind of community theatre: theatre made with perfect love. There are others for whom theatre on anything less than a professional level will have “the stench of failure”; they’re bitter, they’re angry, and they simply can’t let go of the past. This, I think, is part of where the “amateur” or “community” theatre stigma comes from; the idea that theatre made for pleasure is somehow “lesser than” theatre made for profit.

Let me make one thing clear: you have not “failed” for choosing a life that sustains and supports you. You have not “failed” for choosing a job with a steady paycheck and benefits, that will allow you to work human hours and be able to see your family on the weekends. You have not “failed” for not wanting to put your very soul on the stage eight shows a week for audiences, directors, and critics who may or may not be appreciative. You have not “failed” for refusing to do things that are degrading and/or embarrassing simply because you need to work this week and it’s the only job available right now. And you certainly have not “failed” for choosing to return to the theatre on your own terms, in your own time, in a way that fulfills your desire to make art.

Why is it “bad” or “wrong” to want to make theatre under any circumstances possible? Why is one person’s desire to perform seen as inconsequential or smaller than another’s simply because the first person isn’t being paid for their work and the second is? And what made us “professionals” fall in love with theatre in the first place? It certainly wasn’t the “spectacular” paychecks…

The “community theatre” stigma needs to be put to the side. I’m not saying that you have to sit through every amateur production of Oklahoma! you find in the papers with a willing heart and gracious applause, but let’s at least have some consideration for fellow artists. Everyone walks a hard road; why should we make it harder for each other when the world’s already a cruel place for us theatre types?