>Yesterday, a member of my family passed away. It wasn’t unexpected, it wasn’t tragic (as far as death goes), it just was. People die. It is the ultimate punctuation to life. The period, question mark, or exclamation point to our time here upon this mortal coil.

I got the inevitable phone call (of course while I was driving, ain’t that the way things go?), I cried a little, and then I got to thinking. Here was a man who knew he was going to die. He was in the hospital and all signs were pointing at the hereafter. What does one say in those situations? There’s not much to be done, clearly, when you know you are running out of breathe and that your thought cannot sustain itself to another line. But there is still time for a few more words, a poignant tid-bit, a grand exit perhaps. At the very least one final jab at the world…

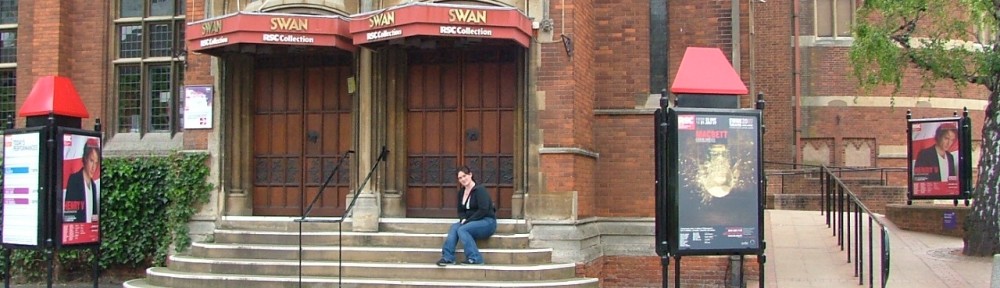

In Shakespeare, people die a lot. It’s the nature of the beast when you write Renaissance tragedy. Sometimes these deaths are expected, sometimes they are not. This passing within my life got me to thinking, what do the characters of the most eloquent man in the history of the English language say when their time is up?

Perhaps the most famous last words are spoken by Hamlet;

If thou did’st euer hold me in thy heart,

Absent thee from felicitie awhile,

And in this harsh world draw thy breath in paine,

To tell my Storie….

O I dye Horatio:

The potent poyson quite ore-crowes my spirit,

I cannot liue to heare the Newes from England,

But I do prophesie th’election lights

On Fortinbras, he ha’s my dying voyce,

So tell him with the occurrents more and lesse,

Which haue solicited. The rest is silence. O, o, o, o.

(Hamlet, V ii, 3832-4847)

Of course, people usually only remember the first bit of this speech. The beautiful part. I can only hope to be half as eloquent on my death bed (or, as in Hamlet’s case, stretched across the ground after having lost a duel and watched my mother be poisoned by my step-father while he lies dying from my own blade). Hamlet recognizes he is dying, he concedes the Country to the invading forces, and then passes in moans of pain. In doing so, Hamlet denies his own decree. “The rest is silence” he says, before letting out increasingly weaker moans of distress. Even in death, Hamlet remains contrary- unable to follow his own orders. Unable to act upon what he has set out to do. He is consistent then, his true self upon the last moment of his life.

Another famous set of last words (though perhaps people don’t realize they are quoting a death rattle when they use them) are given by Richard Plantagenet:

A Horse, a Horse, my Kingdome for a Horse.

(Richard III, V iv, 3840)

This comes from a character who has consistently been able to connive and cannodle anything he wants out of any other character. Here, in death, he is stripped of that ability. He begs for the necessities of battle. Unable to acquire them, he is slaughtered by his own inadequacy (finally). These last words reflect the universe stripping Richard of his unrighteous gains in order to give him his just deserts. It is also a reminder that not everyone can predict their death and give an eloquent speech, sometimes we die pleading for what would save us.

Of course, how could I discuss death without discussing the most famous lovers of all time? Both Romeo and Juliet have memorable closing remarks, though in very different ways. Here is Romeo:

…Eyes looke your last:

Armes take your last embrace: And lips, O you

The doores of breath, seale with a righteous kisse

A datelesse bargaine to ingrossing death:

Come bitter conduct, come vnsauory guide,

Thou desperate Pilot, now at once run on

The dashing Rocks, thy Sea-sicke wearie Barke:

Heere’s to my Loue. O true Appothecary:

Thy drugs are quicke. Thus with a kisse I die.

(Romeo and Juliet, V iii, 2969-2977)

Romeo is a fine balance between the lovely and the practical. He gives his rehearsed speech, he says his goodbye to the world, he even has one of the most dramatic toasts of all time. Then, finished, reality sets in. Much like Hamlet’s “O, o o o”, Romeo is unable to stop at merely the lovely. We find Romeo the human being in his last line- perhaps more revealing and more truthful than anything he had previously spoken. Far from the flowering poetry he spoke but a moment before, Romeo’s final utterance is shiveringly real. Succinct. To the point. It is his life, encompassed.

Juliet is similar:

Yea noise?

Then ile be briefe. O happy Dagger.

‘Tis in thy sheath, there rust and let me die.

(Romeo and Juliet, V iii, 3032-3035)

No long speech. No dramatic toast. Merely the truth. Instructions. Practicality. She has no time for anything else. She is blatant, straightforward and simple, yet poetic. There is nothing brutal about Juliet’s last words. They are kind, gentle, personifying the dagger as something to be rejoiced in rather than feared. It will free her, let her die rather than cause her to die. Juliet releases life as simply as an exhale and nearly as silently.

A less famous parting speech is spoken by Antony:

The miserable change now at my end,

Lament nor sorrow at: but please your thoughts

In feeding them with those my former Fortunes

Wherein I liued. The greatest Prince o’th’world,

The Noblest: and do now not basely dye,

Not Cowardly put off my Helmet to

My Countreyman. A Roman, by a Roman

Valiantly vanquish’d. Now my Spirit is going,

I can no more.

(Antony and Cleopatra, IV xv, 3062-3070)

Antony’s last words also mirror his life. They are strong, practical, and giving. He counsels his friends to remember him in a happier time, a mightier time. He turns the thoughts of Cleopatra to himself at his prime. He eulogizes himself, summing his life up in a necessarily succinct piece. Antony is not terse, but he certainly isn’t a Romeo. No flowers for him, but rather marble monuments. He dies a warrior and a prince. Though in the arms of his lover, he does not die swooning. He simply stops. He can no more.

Another warrior who exits the stage in a flight of glory is the notorious and infamous Macbeth:

I will not yeeld

To kisse the ground before young Malcolmes feet,

And to be baited with the Rabbles curse.

Though Byrnane wood be come to Dunsinane,

And thou oppos’d, being of no woman borne,

Yet I will try the last. Before my body,

I throw my warlike Shield: Lay on Macduffe,

And damn’d be him, that first cries hold, enough.

(Macbeth, V viii, 2468-2475)

MacB actually runs off the stage fighting. He curses, spits, fights, and the next we see of him Macduff is carrying his head to the assembled Scottish Lords. This is again a character in the pinnacle of his life at the moment before his death; he is bright, bold, arrogant. He knows he will lose this battle, but he does not run. He throws up his shield and taunts his impending doom.

But what are Macbeth’s other choices? He certainly cannot grow anymore (as he is already King), he may fade back into obscurity rotting in some dungeon somewhere, but his story is over. Byrnane Wood has come to Dunsinane, the witches’ prophecies have all been fulfilled. There is no more destiny for Macbeth, no other part of the story for him. He must die, he has no choice in that. His only choice is how he does die.

So what will I say when facing down my death? Will I have flowery poetry, be begging for the necessities of life, be ready to face the reaper head on, eulogize myself? Will I find some truth about the deepest core of my humanity in that moment, or will I just fade into obscurity? Will it be offstage or onstage? Or will someone simply announce in the fifth act that “his commandment is fulfilled that Rosincrance and Guildensterne are dead” (Hamlet, V ii, 3864-3865). I don’t think there are any answers to these questions until the moment of their certainty, and I hope to be asking them for many years to come before that certainty arrives.

I will conclude this little jaunt into the macabre with a thought from Cymbeline. When Guiderius and Arviragus set Imogen (as Fidele) in her tomb in IV ii (lns 2576-2600), they speak the following poem because they have no voices to sing. My own voice does not feel the jubilation to be lifted into song at present. I am tired. I am sad. So, once again, I will rely upon Shakespeare to sing for me.

Feare no more the heate o’th’Sun,

Nor the furious Winters rages,

Thou thy worldly task hast don,

Home art gon, and tane thy wages.

Golden Lads, and Girles all must,

As Chimney-Sweepers come to dust.

Feare no more the frowne o’th’Great,

Thou art past the Tirants stroake,

Care no more to cloath and eate,

To thee the Reede is as the Oake:

The Scepter, Learning, Physicke must,

All follow this and come to dust.

Feare no more the Lightning flash.

Nor th’_all-dreaded Thunderstone.

Feare not Slander, Censure rash.

Thou hast finish’d Ioy and mone.

All Louers young, all Louers must,

Consigne to thee and come to dust.

No Exorcisor harme thee,

Nor no witch-craft charme thee.

Ghost vnlaid forbeare thee.

Nothing ill come neere thee.

Quiet consumation haue,

And renowned be thy graue.