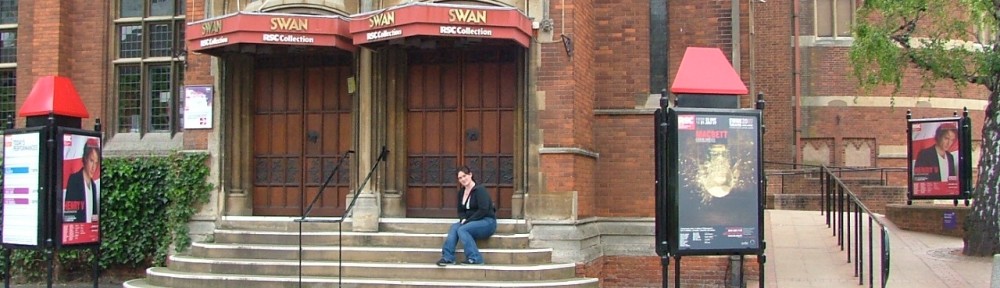

Thanks to Joss Wheedon, it’s been a Much Ado summer. Without any intention of collecting an exclusive list of Much Ados in the New England area, I’ve personally seen four productions so far (two full productions, the film, and one staged reading). Since I don’t have any more on the docket (unless something unexpected pops up, which it might), I thought I might take a moment to make some general observations about the play from my privileged Much Ado-steeped dramaturgical brain while the shows were fresh in my mind. I suppose this could also serve as a basic primer for theatre makers looking to create a production of Much Ado and not looking to hire a dramaturge (big mistake, but the benefits of having someone around to serve that role are fodder for another post).

1) The most hard and fast rule about producing Much Ado About Nothing is that your Beatrice and Benedick ABSOLUTELY have to work. They essentially carry the production and without them, you’re sunk. I’ve seen some tolerably good performances this summer, but none that were well matched (one show had a strong Beatrice and a weak Benedick, another show vice versa, etc.). These actors need to be charming and deep. The audience needs to love them despite their quirks. They need to be experts with the language. They need to have chemistry with each other. Lining up these factors is nearly as difficult as convincing the stars to align (especially in the world of amateur theatre where your talent pool is your talent pool and there’s not much you can do about it), but vital to the health of your production. Trust me, this will make or break your show.

2) The part of Hero is perhaps the most difficult part in the show to play (Claudio and Dogberry make close seconds). Honestly, one of the strongest performances of Hero I’ve ever seen was performed by a dressmaker’s dummy passed around to various cast members when Hero herself needed to be. There’s a danger of making Hero too ingénue. She absolutely has to be sweet and pretty and obedient, but she has some fire in her that, if allowed to come out, will add dimension to your production. Think about the gulling of Beatrice; Hero is both smart and saucy (she demonstrates this as well in the ball scene when she sasses the masked Prince). A further point of caution: if her part is cut too severely, she comes off as nothing but an airy fairy sugar-spun object. Careful with this one.

3) Dogberry is extremely difficult to make read to a modern audience. If he’s played too smart, he doesn’t make sense. If he’s played with too much status, he doesn’t make sense. If he’s played by someone who does not have an absolutely command of the language, he doesn’t make sense. Dogberry and the watch need to come off as well-meaning, sweet, regular guys whose logic sometimes doesn’t match our earth logic. The most important thing to remember is that Dogberry is striving, with every fiber of his being, to have status he just doesn’t know how to make it work. He’s trying, by virtue of “being is becoming”, to make himself into a real leader and a true soldier… he just can’t quite get there.

4) The third-act wedding scene needs to be a punch in the gut bordering

some really cool shots of books I took this summer because I don’t have anything else to put here

on melodrama. This scene changes the entire tide of the production. Suddenly we go from a rollicking comedy to something which (if ended prematurely) could more resemble a classic tragedy. You really need to set this change of pace up for an audience and draw them into the mood. Claudio really needs to manhandle Hero. Hero really needs to have a reason to faint and look dead. Beatrice really needs to have a reason to be weeping into the next scene. These are strong, dynamic characters capable of extreme emotional manipulation and extreme emotional reaction; if this is not expressed, your production suddenly no longer has purpose. The entire second half doesn’t have a reason to exist, and (most importantly), my favorite scene in the canon falls flat. If there’s no real given reason for Beatrice’s famous utterance, the audience just won’t buy it.

5) Speaking of duels, if you choose to modernize your production make sure the gender and status dynamics still make sense. See my previous post on this point.

6) Another note about status: the Prince needs to have an easy sort of control over every situation he’s placed in. Though a guest in Leonato’s house (and in act four certainly emotionally indebted to Leonato), he is still the Prince. Despite anything which may be happening (including, as he believes, the death of Leonato’s daughter which is at least in part his fault), he must maintain that status. This is particularly important because modern American audiences do not understand status. If you work hard through the course of your production to create status, any chink will make the entire illusion crumble. Don’t give the audience a reason not to buy into your world.

7) For god’s sake can someone please come up with a creative solution to Don John? I have yet to see anyone in the role who doesn’t make me think of Keanu (though granted, Sean Maher’s performance came close to banishing this image – he was pretty sexy). Textually, he’s a problem. He’s obviously brooding and quiet, angry with his brother and ready to revel in any misfortune that he can cause because of this. But is there any way to make this into a villain that we love to hate? I’m so sick of stoic-faced Princes who turn into whining, petulant grumps in the presence of their henchmen only to plot a revenge which they obviously take no joy in. Someone, please, fix this and invite me to your show so I can stop wondering if anyone will get the Prince a surfboard.

This is by no means an exhaustive list of things I see, just bits which tackle some of the play’s bigger issues. If you’re planning a production and are looking for a dramaturge, I highly encourage you to contact me. I always love to participate in crafting good Shakespeare and this play has a special place in my heart.

And now, back to the comps grind.