>

Feminism is a topic that comes up a lot at Rutgers. Our department was a pioneer in feminist criticism, many of the professors are feminist critics, and we house a thriving concentration in women/gender studies which ensures that many of the students are feminist critics as well.

For me, feminism and feminist criticism is hard to talk about. Mostly because I’m still unsure where I stand on the matter. I used to think of myself as above the argument; so they’re women, who write stuff, why is everyone making such a big deal of it? Then I realized that I was a part of the argument, I just struggled fruitlessly against it. There are innate topics of discussion regarding women and literature, women in literature, and women talking about literature I just didn’t want to talk about them. I slowly came to wonder why that was. Though I’ve made some progress in answering this question for myself, it’s not enough that I can truly articulate fully my ideas on it. Suffice to say that I tend to play every side of the field when women come up in classroom conversation. This is mostly because I hate when a roomful of smart people agree on something… though I will admit that I like to see them twitch when I suggest that a biological imperative began the tradition of woman as home-maker and perhaps that tradition warrants some respect as a valid way to live one’s life.

In any case, we were discussing Wollstonecraft in Romantics last night and one of the girls made a comment to the following effect, “In Wollstonecraft’s time, men had to tell women they were beautiful because it was the only socially acceptable way to validate them”.

Well isn’t that just a mouthful?

I could hear my personal demons whispering behind my shoulders. They had somehow picked the lock on their well-chained closet and, given strength by the aforementioned suggestion, had returned to haunt me.

I flashed back to a conversation I had had with an ex of mine. He took great pride in the fact that all of his friends, upon meeting me, would clap him on the back and say “good job”. Having recalled said meetings I realized that “meet” was a relative term. We were ships in the night with nothing more than a handshake and a hello. These people didn’t know me. They had only seen me. Their complements weren’t because of my ability to recite sonnets at whim, my wit as a conversationalist, my fabulous writing talents or my impeccable modesty, they were simply based upon a superficial visual appraisal. His friends thought I was pretty and, thereby, a catch. And that made him happy.

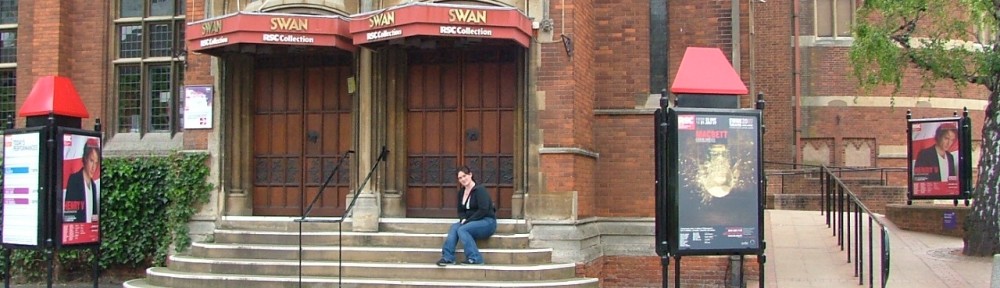

Whoa. WHOA. As much as I like to dress up, play with makeup, wear heels and look nice, as much as I like to play arm candy for any given evening at the theatre, as much as I joke that I’d happily be a trophy wife for the right millionaire, something about the situation did not sit well with me. I couldn’t blame his friends, they were boys and well, boys will be boys. But I did expect something more from him. Some modicum of respect for not just how my hair looked, but what it hid. Some nod towards how capable I am. Some witty addition from him to the effect of “yea, and she can parse a sentence too!”

Don’t get me wrong, it wasn’t that he didn’t acknowledge and respect my capabilities, it was just that he didn’t think it was important to complement them. He would send me papers to edit, he would ask my opinion on poetry, but he wouldn’t tell his friends that I graduated NYU with Latin Honors.

This, I have found, is not an uncommon occurrence. Complements given to women still run in the vein of visual appreciation rather than intellectual satisfaction. We are much more likely to hear (and, in turn, say) “I love your outfit!” than “I love your prose!”. Somehow, society expects this of us. Especially as a woman, there is pressure to wear pretty dresses and heels so that some man can tell me I look nice when I’d much rather hear about how insightful I am.

A very dear friend of mine is currently teaching Freshman Comp at Rutgers. When one of her friends found out that she had received the position, said friend’s immediate reaction was “You’re going to be the hottest professor ever!”. My friend the professor explained to me the sour taste this left in her mouth. Rather than complementing her capabilities as a teacher, her writing, or her thoughtfulness, it was instead all about how she looked.

I’m not saying there’s no place for such things. Every woman wants to hear that she’s pretty once in a while. But those are snacks, unsubstantial and unsustaining. They are as superficially pleasing as they are insightful.

Moreover, “beauty” is an aesthetic judgment and ultimately random. I can’t control my genetics. I didn’t choose the way I look. Maybe I chose how I augment these looks with clothing, shoes, makeup, accessories – but that is nominal. Clothes don’t make the girl. My mind? That is something I work at. Every day, every hour, I work hard to be smart. I’d much rather hear about how that work has paid off than how some proteins randomly aligned themselves before I even had consciousness to care about it.

In short: tell the academic, big-brained woman in your life that she’s pretty sometimes, but if you really want to tell her something that will make her happy, tell her she’s smart. Dote on the size of her medulla, not the amount of time she put in at the salon. Paddle in her prose, not her choice in dresses that evening. Most importantly, don’t just tell her that she’s a genius, tell her why you think she’s a genius. It shows her that you actually care enough to look deeper than her skin.